Introduction

This vignette demonstrates the basic structure and creation of a

spatial phylogenetic data set, which is the first step of any analysis

using this R package. Spatial phylogenetic analyses require two

essential ingredients: data on the geographic distributions of a set of

organisms, and a phylogeny representing their evolutionary

relationships. This package stores these data as objects of class

'phylospatial'.

The core idea of spatial phylogenetics is that analyses account for every every single “lineage” on the phylogenetic tree, including terminals and larger clades. Each lineage has a geographic range comprising the collective ranges of all terminal(s) in the clade, and it has a single branch segment whose length represents the evolutionary history that is shared by those terminals and only those terminals. When calculating biodiversity metrics, every lineage’s occurrence in a site gets weighted by its branch length.

In this vignette, we’ll create a lightweight example of a

phylospatial object, look through its components to

understand how it is structured, and then demonstrate some more nuanced

use cases with real data. Finally, we’ll show how

phylospatial objects can also be used for traditional

non-phylogenetic biodiversity data analyses, in cases when incorporating

a phylogeny is impossible or undesirable.

A minimal example

Let’s begin by creating a simple phylospatial object. To

do this, we use the phylospatial() function, which has two

key arguments: tree, a phylogeny of class

phylo, and comm, a community data set

representing the geographic distributions of the terminal taxa (usually

species). In the code below, we simulate a random tree with five

terminal taxa, and a raster data set with 100 grid cells containing

occurrence probabilities for each terminal, with layer names

corresponding to species on the tree. (A differentiating feature of the

phylospatial library is that it supports quantitative data

types like probabilities or abundances, in addition to binary community

data.) Then we pass them to phylospatial():

library(phylospatial); library(terra); library(ape); library(sf)

# simulate data

set.seed(1234)

n_taxa <- 5

x <- y <- 10

tree <- rtree(n_taxa)

comm <- rast(array((sin(seq(0, pi*12, length.out = n_taxa * x * y)) + 1)/2,

dim = c(x, y, n_taxa)))

names(comm) <- tree$tip.label

# create phylospatial object

ps <- phylospatial(comm, tree)

ps

#> `phylospatial` object

#> - 8 lineages across 100 sites

#> - community data type: probability

#> - spatial data class: SpatRaster

#> - dissimilarity data: noneStructure of a phylospatial object

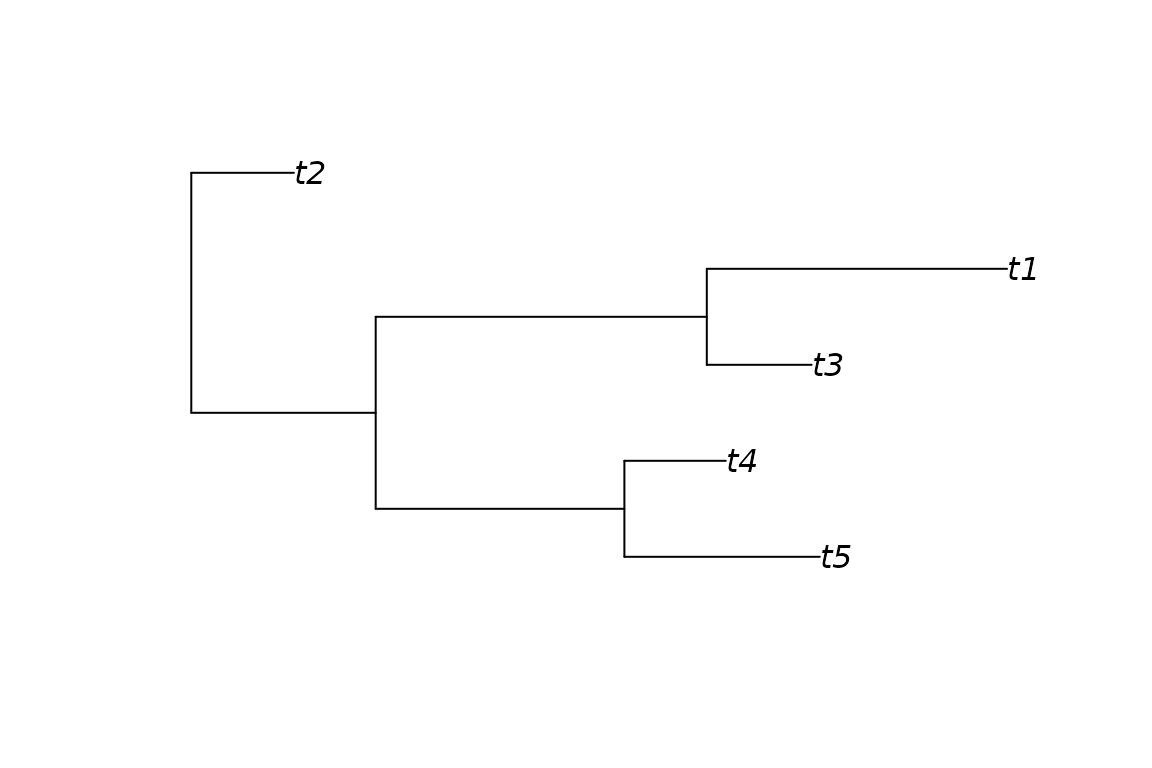

Phylogeny

Our phylospatial object is a list with six elements.

Let’s look at each of these in turn, starting with the

tree. This is the phylogeny we simulated, a tree of class

phylo with 5 tips and 3 larger clades. Note that the branch

lengths of the input tree are scaled to sum to 1. We can use

plot() function to view the tree.

names(ps)

#> [1] "comm" "tree" "spatial" "data_type" "clade_fun" "dissim"

ps$tree

#>

#> Phylogenetic tree with 5 tips and 4 internal nodes.

#>

#> Tip labels:

#> t5, t4, t3, t1, t2

#>

#> Rooted; includes branch length(s).

plot(ps, "tree")

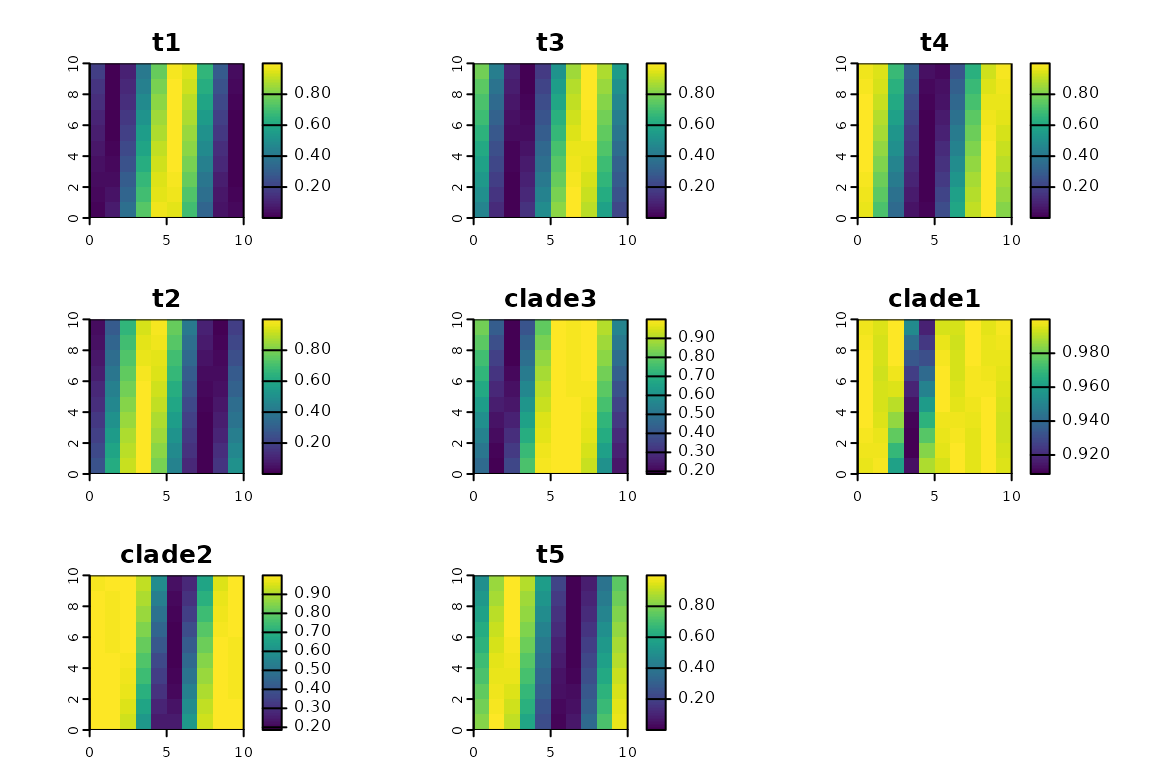

Community matrix

The other key component is comm, which is a

matrix containing occurrence data. Although we supplied

community data as a raster, it’s stored here as a matrix, with a row for

each grid cell and a column for each taxon. Let’s take a look at the

matrix. We can also plot the community data, which re-casts

it as a spatial data set (a raster, in this case).

head(ps$comm)

#> clade1 clade2 t5 t4 clade3 t3 t1

#> [1,] 0.9980319 0.9889042 0.5000000 0.97780849 0.8226247 0.781536164 0.18807934

#> [2,] 0.9953701 0.9919546 0.8428239 0.94881279 0.4245239 0.421627315 0.00500815

#> [3,] 0.9997640 0.9997100 0.9991060 0.67560320 0.1861159 0.104363637 0.09127841

#> [4,] 0.9517871 0.9194606 0.8838080 0.30684210 0.4013750 0.002378797 0.39994761

#> [5,] 0.9172596 0.5786829 0.5596673 0.04318460 0.8036150 0.171166120 0.76305863

#> [6,] 0.9936764 0.2254502 0.2030598 0.02809548 0.9918358 0.518882839 0.98303074

#> t2

#> [1,] 0.03467274

#> [2,] 0.28671168

#> [3,] 0.65480785

#> [4,] 0.93866795

#> [5,] 0.98383430

#> [6,] 0.76573040

plot(ps, "comm")

We can see that in addition to our 5 terminal taxa, the data set also

includes geographic ranges for the 3 larger clades. Internally, the

phylospatial() function constructs ranges for every

multi-tip clade on the tree, based on the topology of the tree and the

community data for the tips.

The specific way that these clade ranges are constructed depends on

the type of community data being used. The package supports three data

types: "probability", "abundance", and

"binary". Recall that our data were probabilities; we could

have specified that explicitly by setting

data_type = "probability" when we constructed our

phylospatial object, but the function detected this based on the values

in our data set, and we can confirm that it did so correctly by checking

ps$data_type. For probabilities, the default function used

to calculate clade occurrence values gives the probability that at least

one member of the clade is present in a given site. Abundance and binary

data have their own default functions. (You can also override the

defaults by supplying your own clade_fun—for example, if

you had occurrence probabilities that you knew were strongly

non-independent among species, you could specify

clade_fun = max.) The function that was used for a given

data set can be accessed at ps$clade_fun.

Note that you can also specify your own clade ranges to

phylospatial() rather than letting it build them for you,

by setting build = FALSE. You might want to do this if, for

example, you have modeled the distributions of every clade in addition

to every terminal species in your data set.

Spatial data

The spatial component is the last key piece of our

phylospatial object. (The only other element we haven’t mentioned here

is dissim, which is covered in the vignette on beta

diversity.) The spatial component of the object contains spatial

reference data on the geographic locations of the communities found in

each row of the community matrix.

In this example, the spatial data is a raster layer inherited from

the SpatRaster data we supplied as our comm.

You can also supply vector data (points, lines, or polygons) as an

sf object. If the spatial data is in raster, polygon, or

line format, phylospatial will check that all features have

equal area or length, which is an important assumption underlying

various functions in the package.

Also note that spatial data isn’t required; community data provided as a matrix works just fine.

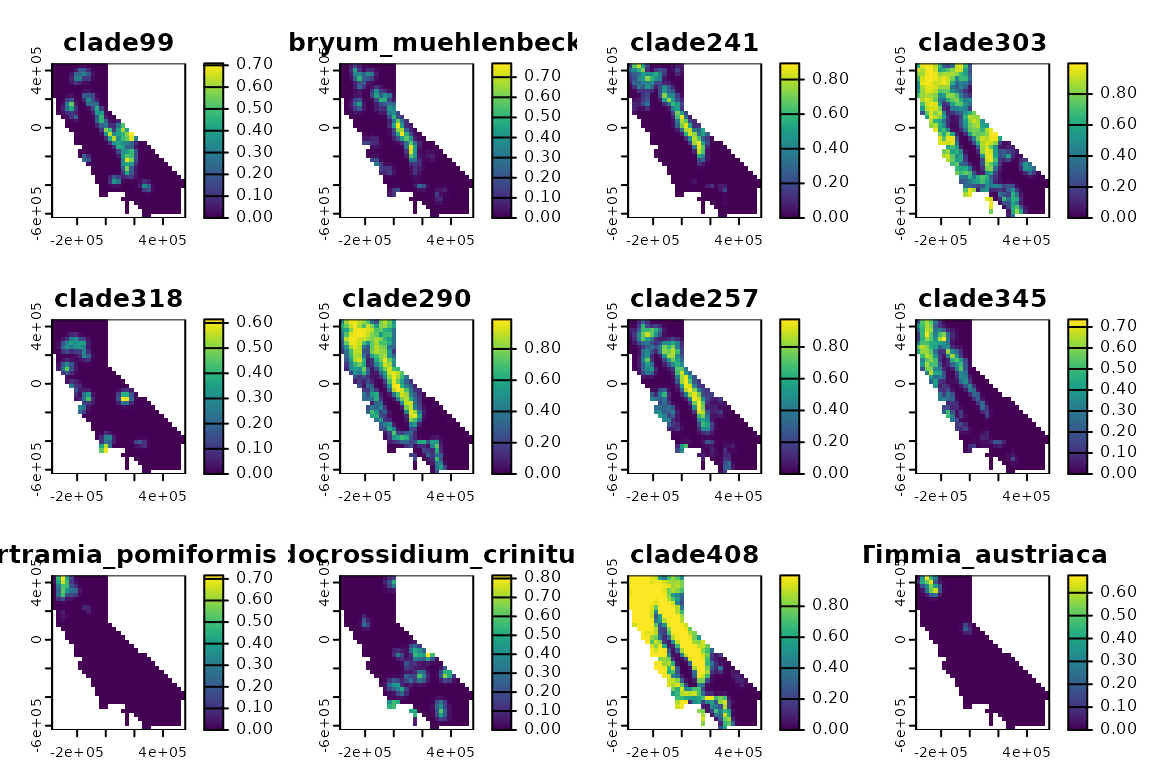

A realistic example

Now let’s look at creating a phylospatial data set using real data.

To do this, we’ll use the example “moss” data set that ships with the

package, representing a phylogeny and modeled occurrence probabilities

for several hundred species of moss in California. The function

moss() returns a pre-constructed phylospatial

object based on these data, but here let’s build one from scratch. In

the code below we’ll load a raster data set with a layer of occurrence

probabilities for each species, and a phylogeny representing their

evolutionary relationships. We’ll then pass these to

phylospatial().

moss_comm <- rast(system.file("extdata", "moss_comm.tif", package = "phylospatial"))

moss_tree <- read.tree(system.file("extdata", "moss_tree.nex", package = "phylospatial"))

ps <- phylospatial(moss_comm, moss_tree)

plot(ps, "comm")

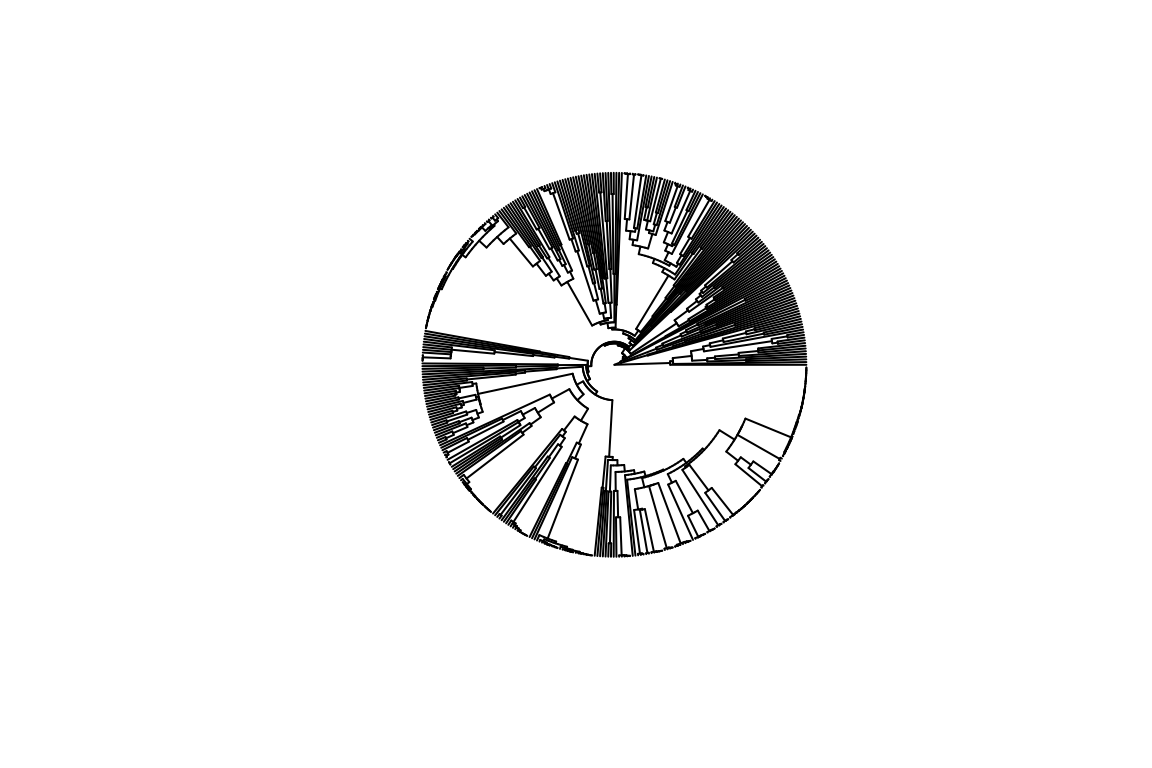

plot(ps, "tree", type = "fan", show.tip.label = FALSE)

Non-phylogenetic data

While the phylospatial library is obviously designed for

phylogenetic analyses, it’s worth noting that it also supports

non-phylogenetic analyses. In cases where a phylogeny is unavailable or

where a traditional species-based biodiversity analysis is desired, you

can create a data set by calling phylospatial() without

providing a tree. All major functions in the package will still work,

and will assume that the taxa in comm are independent and

equally weighted.

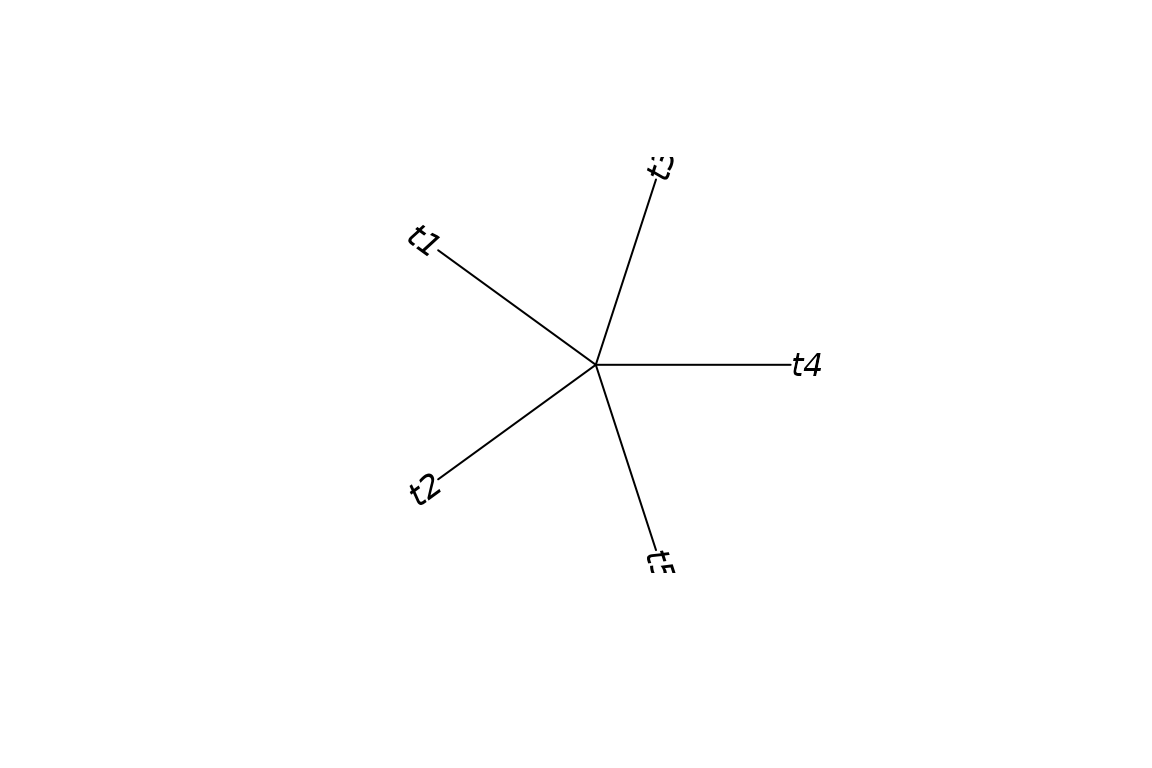

In fact, traditional species-based methods can actually be considered

a specific case of more general phylogenetic methods, in which species

are assumed to be connected on a “star” phylogeny with a single polytomy

and equal branch lengths. In phylospatial, support for

non-phylogenetic data is implemented by creating a star phylogeny if no

phylogeny is provided by the user. Here’s how this looks for the simple

community data we created above:

ps <- phylospatial(comm)

plot(ps, "tree", type = "fan")